Did anyone see this exhibition in NYC last year?? Here’s an excellent article by on Hyperallergenic.com:

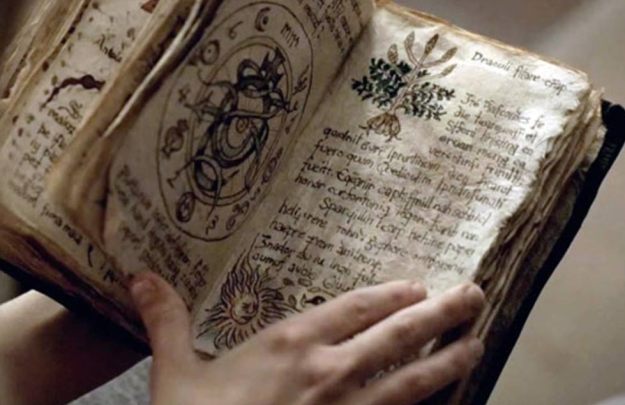

A strange visual language developed from the 18th to the 20th

century behind the closed doors of American secret societies. It’s a

languae made up of all-seeing eyes, ominous skulls, hourglasses, arrows,

axes, and curious hands holding hearts. Each of these icons was deeply

symbolic for the thousands of people — mostly men — who participated in

rituals of borrowed meaning, where ancient Egypt, biblical Christianity,

and some homegrown amusements like wooden goats on wheels met the rise

of American folk art. The American Folk Art Museum’s (AFAM) Mystery and Benevolence: Masonic and Odd Fellows Folk Art from the Kendra and Allan Daniel Collection examines this often hidden history through its arcane artifacts.

Mystery and Benevolence was curated by Stacy C. Hollander,

chief curator and director of exhibitions at AFAM, and Aimee E. Newell,

director of collections at the Scottish Rite Masonic Museum and Library.

It features over 200 objects recently donated to the museum by Kendra

and Allan Daniel, who spent three decades buying up the

once-secretive art. Installed in the museum, the objects are an

exuberant display of the “golden age” of Masonic and Odd Fellows

objects, when American decorative and folk art merged with the need

for a sense of belonging in the new country.

“After becoming an independent nation in the 1780s, America was

seeking to establish its own cultural identity; Freemasonry offered a

source of images that resonated with the new nation’s values of equality

and liberty,” Newell writes in the accompanying catalogue.

“Freemasonry’s visual language and American style began to intersect

almost as soon as victory over the British was declared, and continued

to adapt as the nation grew and the fraternity evolved. ”

Much of the exhibition contextualizes this long-hidden art in the

history of the societies, such as their charity work. The Odd Fellows,

formed in 18th-century London, were organized as a benevolent group to

support the sick, orphans, and those who died without money for a

funeral. One of their mission statements is proclaimed in red and gold

on a large wooden sign: “Bury the Dead.” There are also axes indicating

how the Odd Fellows saw themselves as “pioneers in the pathway of life”;

staffs topped with a heart in the hand were a reminder to be open to

others.

Similarly, even the more ghoulish imagery had some meaning connected

to charity, and selflessness. The skulls, hourglasses, and

skeletons holding shields painted with the word “fidelity” were all

reminders of mortality, and how one’s brief time on earth could be

better dedicated to others. Reverend Aaron B. Grosh wrote in 1853’s The Odd Fellow’s Manual:

“Only the good or evil of our lives will survive us on earth, to draw

down on our memories the blessings of those we have aided, or the

contempt and reproach of those we have injured.”

Mystery and Benevolence: Masonic and Odd Fellows Folk Art from the Kendra and Allan Daniel Collectioncontinues at the American Folk Art Museum (2 Lincoln Square, Upper West Side, Manhattan) through May 8.

and…